Last Updated on April 4, 2021 by OJ Maño

December 12, 1888 – During Governor-General Valeriano Weyler’s visit to Malolos, he requested to hold an audience with the townsfolk. Upon getting word of this, Teodoro Sandiko wrote a Spanish letter addressed to the governor-general and asked the women he had been teaching to sign it. The letter, a plea for schooling, was signed by 20 women of Malolos, who went to the convent to present the letter to Weyler in the afternoon. One of their leaders, Alberta Uitangcoy, handed him the letter.

The women then waited around for a response, compelling the governor-general to read it on the spot. The friars headed by Fr. Felipe Garcia, the Spanish parish curator of the Malolos Church (now known as the Minor Basilica of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception or Malolos Cathedral), highly objected to their plea, which heavily influenced the governor-general’s decision that turned down the petition initially.

However, in defiance of the friar’s wrath, these young women of Malolos bravely continued their clamor to have proper schooling — a thing unheard of in the Philippines in those times.

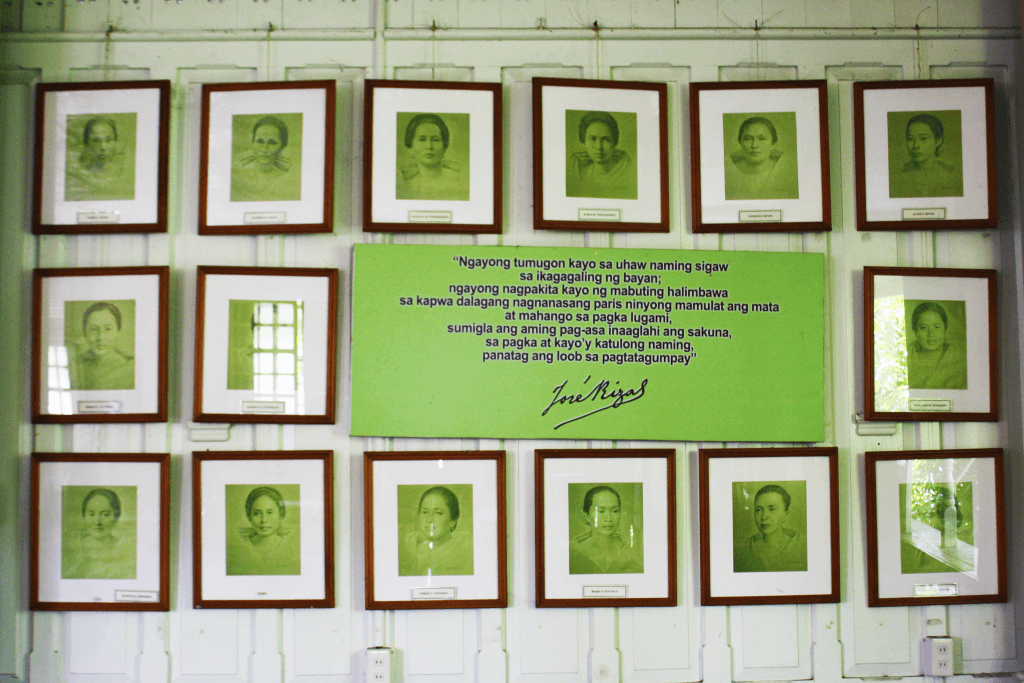

On February 22, 1889, Jose Rizal wrote a Tagalog letter entitled “Sa Mga Kababayang Dalaga Sa Malolos,” praising and supporting their plan of putting up a night school.

Why did Rizal write them a letter?

Teodoro Sandiko irked the friars for supporting women’s education and promoting liberal ideas. He was accused of being a filibuster and a subversive; that’s why he had to sail to Hong Kong later in December 1888 to escape persecution. He then went to Spain to continue his law school at the Universidad Central de Madrid (now called Universidad Complutense de Madrid or the Complutense University of Madrid). Soon after, he joined the Propaganda Movement, and on February 15, 1889, he agreed to manage La Solidaridad together with Marcelo del Pilar, Mariano Ponce, and Graciano López Jaena.

Sandiko told del Pilar and López Jaena the inspiring story about the 20 brave young women of Malolos. On February 17, 1889, Del Pilar requested Jose Rizal to send a Tagalog letter to these brave women of Malolos. Although busy in London annotating Morga’s book, Rizal penned his famous very long letter and sent it to Del Pilar on February 22, 1889, for transmittal to Malolos.

Rizal was motivated to write the letter because his friend, Marcelo H. del Pilar, urged him to do so; and because Rizal was really impressed by their bold move and aspiration to study and be educated. Remember that this is a time when women were generally stereotyped as plain housewives, without the need for formal education and an active role in society.

Did they meet Jose Rizal in-person?

Yes. Local historians and even direct descendants of the brave women of Malolos attested that Dr. Rizal met the wonderful ladies in-person on one or two occasions during his short visits to Malolos.

According to history books, Dr. Jose Rizal visited Malolos a few times on different affairs. Moreover, on June 27, 1892, Rizal went to Malolos and met with Don Jose Bautista and other prominent Maloleños in his Mansion along the Pariancillo (now called Santo Niño) street. Rizal was there to pitch his plan to launch a propagandist organization called La Liga Filipina.

Read Kamestizuhan District: Home of the Women of Malolos article

Who are the women of Malolos?

The Women of Malolos consisted of 20 women from the sangley mestizo clans of the town: The Tanchanco, Reyes, Santos, Tantoco, and Tiongson families of native, Chinese, and Spanish ancestry. A few of them had received education at a college like Colegio de la Concordia. They all lived in the Chinese neighborhood of Pariancillo, Malolos. They were all related, by either blood or affinity, and were friends as well.

Sangley, Sangley mestizo, mestisong Sangley, mestizo de Sangley or Chinese mestizo is a term used in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial period to describe or classify a person of mixed Chinese and Filipino ancestry.

During the Philippine Revolution against Spain, many of them aided the revolutionaries. Later, many of them were involved in women’s socio-civic organizations. For most, their main commitment was to the family. All of them were accomplished at keeping house; in fact, they specifically requested a night school as they were all busy with household tasks during the day, although none of them were married at the time. Whether married or not, throughout their lives, most of these women of Malolos ran organized households, whether for their own family or parents or siblings. A number of them were involved in the business as well. The individual women are described briefly below by family.

Elisea Tantoco Reyes – Known by the nickname “Seang,” she was 15 when the women of Malolos approached Weyler. Though she did not go on to any higher education, she spoke Spanish well. Her father was a reformist who was persecuted by the Spanish government during his term as gobernadorcillo. Along with her family, she aided the revolutionary army by providing supplies.

She joined the National Red Cross formed in 1899 by Emilio Aguinaldo’s wife during the Philippine-American War. In 1906, she became a member of the Pariancillo chapter of the Asociacion Femenista de Filipinas (AFF) formed by the sisters of Rizal, which later became the Club de Mujeres. She married Gregorio Galang at the age of 31 and had 1 child. She remained in her family’s home in Malolos for most of her life. She died in 1969 at the age of 96.

Juana Tantoco Reyes – The younger sister of Elisea, she was called “Anang” and was 14 at the time. Along with her family, she aided the revolutionary army by providing supplies. She did not have higher education, and she later married her 4th cousin, Mariano Tiongson Buendia. Sadly, she died 2 months after giving birth to their daughter in 1900.

Leoncia Santos Reyes – The 1st cousin of Elisea and Juana’s father, was 24. She was a fluent Spanish speaker, and at merely 17, was noted as a property owner. She married her first cousin Graciano T. Reyes, a reformist and a friend of Sandiko’s, in 1889. They had 13 children, and she ran a store while her husband attended a business of his own. She was widowed around 1930. She died in 1948 at the age of 84.

Olympia San Agustin Reyes – The half-sister of Leoncia, she was 12 years younger. She was the youngest of the women to sign the letter, being only 12 at the time. She eventually married Vicente T. Reyes, the brother of Elisea and Juana. The couple had 9 children, but Olympia died after giving birth to twins at 34.

Rufina T. Reyes – Though she did not sign her family name, Rufina certainly was one of the brave women of Malolos as the classes were eventually held in her house. At that time, she was 19. She was a first cousin of Elisea and Juana and, like them, a niece of Graciano T. Reyes. Along with her family, she aided the Katipunan. She joined the Red Cross and was a founding member of the Pariancillo, Malolos committee of the AFF. She died at the age of 40.

Eugenia Mendoza Tanchangco – Nicknamed “Genia,” she was then 17. Her father was the great Capitan Tomas Tanchanco, the gobernadorcillo of Malolos from 1887-1889. She studied at Colegio de la Concordia in Manila. It is recorded that she met Rizal at a baptismal party in Malolos in 1888, before Weyler’s encounter. When she was 19, she married Ramon Vicente Reyes, a municipal official, and 11 children. She was widowed in 1935 and died in 1969 at the age of 98.

Aurea Mendoza Tanchangco – Eugenia’s younger sister, she was 16 during the encounter with Weyler. Like her sister, she was sent to La Concordia, living with relatives in Binondo while finishing her education. She was excellent in reading, writing, and speaking Spanish, and was considered the brightest student in the school of the women of Malolos. With her family, she gave aid to the revolutionary army. In 1898, she married a former Spanish Army doctor, who began courting her in her textile shop.

Her husband, Eugenio Hernando, later became an officer in the Philippine Army under Aguinaldo and Director of the Bureau of Public Health under Manuel L. Quezon. They had 14 children, and Aurea became a member of the Club de Mujeres. She died of stomach cancer within 4 months of her husband’s death in 1958. She was 86 years old.

Basilia Villariño Tantoco – Called “Ilyang,” she was 23 at the time. She was Eugenia and Aurea’s second cousin. She studied with private tutors and a college in Manila and was a devout Catholic. In the early 1880s, she resisted the sexual advances of the friar curate of Malolos. She was one of those chosen to lead the group in presenting the letter to Weyler. During the Philippine Revolution, her uncle, father, and 5 brothers were active in the Katipunan. She acted as a courier for the Katipunan, hiding messages in her clothing. During the establishment of the republic in Malolos, she and her brother Juan donated their houses to the government.

Connected by a bridge, they were used to house the office of the Secretaria de Hacienda. A founding member of the Red Cross, she was on its board of directors and headed the 3rd commission. She was a member of the AFF in Malolos as well. In 1917, she set up the Escuela Catolica de Malolos, a pre-school and grade school closed in 1922. As the firstborn and the only daughter in her family, she managed her family’s extensive properties after the death of her parents until she died in 1925 at the age of 60.

Teresa Tiongson Tantoco – First cousin of Basilia’s and, like her, second cousin to Eugenia and Aurea, “Esang” was 21 at the time of the encounter Weyler. She was the eldest in her family. She also joined the Red Cross and the AFF. In the AFF, she was treasurer of the 1st Pariancillo committee. She had a daughter out of wedlock in 1897, and she married Julian Reyes in 1912 when she was 45. She was over 74 when she died in 1942.

Maria Tiongson Tantoco – Teresa’s younger sister, she was then 19. She married Lino Santos Reyes, who was the Cabeza de Barangay. The Secretaria de Exterior of the Republic of Malolos was housed in their home. She became a member of the AFF. She had a dozen children and died at the age of 44 after an operation.

Anastacia Maclang Tiongson – She was 1st cousin to Teresa and Maria Tantoco and second cousin to Eugenia and Aurea Tanchangco and Basilia Tantoco. Nicknamed “Taci,” she was 14 at the time. She and her family aided the revolutionaries by providing supplies. She later joined the Red Cross. In 1899, she fled the American invasion of Malolos with her family.

They resettled in Dagupan, where she opened the first movie house in the province. A shrewd businesswoman, she was also the first and sole distributor of San Miguel Beer in Dagupan, distributing around the whole of Pangasinan. She sold ice as a companion business, and became a large landowner. At the age of 36, she married Vicente Torres and had 1 surviving daughter. She died of appendicitis in 1940, when she was 66.

Basilia Reyes Tiongson – She is known to be a personal acquaintance of Marcelo del Pilar, based on his letters. A first cousin of Anastacia Tiongson and Maria Tantoco, she was called “Ylia” and was then 28.

Paz Reyes Tiongson – One of those who signed the letter with only her first name, she was the younger sister of Basilia and, like her, known to have been acquainted with Del Pilar. She was 24 at the time of the encounter with Weyler. Unfortunately, she was unable to attend the official classes due to illness. She died early in 1889, probably of a heart ailment.

Aleja Reyes Tiongson – The younger sister of Basilia and Paz, “Ejang,” was 23 at the time. She also signed only her first name on the letter.

Mercedes Reyes Tiongson – Known as “Merced” for short, she was Basilia, Paz, and Aleja’s youngest sister. She was then 18 and was the one who organized the group to open a school for learning Spanish. During the Philippine Revolution, she aided the Katipunan by sending supplies. She took over the family property management after the deaths of her father and older siblings, overseeing the lands on horseback.

In 1903, she married Sandiko, who became governor and senator for 2 terms each. The couple’s 2 sons died when they were barely out of infancy, so they adopted her goddaughter. Mercedes was one of the founding members of the Red Cross. On the national board of directors of the Red Cross, she headed its 2nd commission. She was a founding member of the AFF. She died in 1928 of a heart attack following an asthmatic attack, at the age of 58.

Read More about Senator Teodoro Sandiko from the 7 Notable Philippine Senators From Bulacan — From the 1900s to Today article

Agapita Reyes Tiongson – The youngest sister of Basilia, Paz, Aleja, and Mercedes Tiongson, she was 16 at the time. “Pitang,” as she was known, was especially close to Mercedes, and like her, aided the revolutionary army. She studied at Colegio de Santa Isabel. She married Francisco Batungbakal when she was 42. The couple had no children, so she raised her goddaughter. In 1937, when she was 65, she died from a diabetic coma. Much of her property was willed for the construction of a hospital, which was never built.

Filomena Oliveros Tiongson – Known as “Mena,” she was 3rd cousin to the Reyes- Tiongson sisters, Anastacia Tiongson, Leoncia Reyes, and the Tantoco sisters. She was around 23 when the letter to Weyler was presented. It is recorded that while the new friar-curate was calling on her sisters in 1889, she heard about it while in her uncle’s house across the street from her home.

She immediately took a knife and went home to participate in the conversation with the friar, all the while pretending to clean her nails with the knife. With her sister Cecilia, she wittily parried the friar’s accusations regarding such matters as their rare visits to the church, infrequency of confession, and gossip that they had eaten meat on Holy Thursday.

She married Eladio Adriano in 1892. The couple had 3 surviving children. Filomena aided the Katipunan and the Malolos Republic and joined her husband and sisters in petitioning Governor-General Polavieja for Rizal’s clemency in 1896. She maintained a close friendship with the Rizal sisters, and became a founding member of the AFF of Malolos. She helped with family business undertakings and the management of their landholdings. Blinded late in life, she died suddenly in 1930, when she was about 65.

Cecilia Oliveros Tiongson – One of the women who did not sign her last name was around 21 during the encounter with Weyler. Called “Ylia,” she was the younger sister of Filomena. She was known for her audacious responses in dealing with the friar-curate appointed to Malolos in 1889. When the friar-curate sent the gobernadorcillo to invite Cecilia and her sisters to the convent, Cecilia told him off by saying she could not believe the gobernadorcillo would solicit women for the priest.

When the friar-curate visited her and her sisters, she was joined by her sister Filomena in parrying the friar’s accusations, boldly pointing out among other things that they would have less time to do good deeds and to earn money if they went to church too frequently, that the church only required confession once a year, and that women who visited the friar at the convent in Malolos were considered to have lost their virtue.

She joined Filomena and other relatives in pleading for Rizal’s clemency and remained a friend of the Rizal sisters. With the rest of her family, she helped the Katipunan by sending them supplies. She later became a member of the Red Cross. At age 63, following the death of Filomena, Cecilia married her brother-in-law, Eladio Adriano. She died 4 years later at the age of 67.

Feliciana Oliveros Tiongson – Known as “Cianang,” she was Filomena and Cecilia’s younger sister. She was 19 at the time the letter was presented. She witnessed the exchange between her older sisters and the friar. She was also with her sisters when they went on their knees to plead for Rizal’s clemency and, like them, maintained a friendship with the Rizal sisters. Along with her family, she aided the Katipunan by sending them supplies. She became a member of the AFF. She helped her sister Filomena raise her children and grandchildren. Highly religious, she taught the children prayers in Spanish and gave them lessons in the catechism and the rudiments of reading and arithmetic. She died in 1938 at the age of 70.

Alberta Santos Uitangcoy – Called “Iding,” she was the first cousin of Leoncia Reyes. She received higher education at La Concordia. With her strong will, she was chosen along with Basilia Tantoco as the group leader in presenting the letter to Weyler. At that time, she was 23. It was she who personally handed the letter to Weyler. She married Paulino Santos, then Cabeza de barangay, the following year. The couple had 9 children. Still, Uitangcoy found time for social involvement, becoming a founding member of the Red Cross and the AFF. After she was widowed in 1927, she took over the administration of the family properties. She died in 1953 at the age of 88, after a long period of debilitation.

Names of the 20 Women of Malolos

- Elisea Tantoco Reyes (1873-1969)

- Juana Tantoco Reyes (1874-1900)

- Leoncia Santos Reyes (1864-1948)

- Olympia San Agustin Reyes (1876-1910)

- Rufina T. Reyes (1869-1909)

- Eugenia Mendoza Tanchangco (1871-1969)

- Aurea Mendoza Tanchangco (1872-1958)

- Basilia Villariño Tantoco (1865-1925)

- Teresa Tiongson Tantoco (1867-1942)

- Maria Tiongson Tantoco (1869-1912)

- Anastacia Maclang Tiongson (1874-1940)

- Basilia Reyes Tiongson (1860-1925)

- Paz Reyes Tiongson (1862-1889)

- Aleja Reyes Tiongson (ca 1864-ca 1900)

- Mercedes Reyes Tiongson (1870-1928)

- Agapita Reyes Tiongson (1872-1937)

- Filomena Oliveros Tiongson (ca 1867-1934)

- Cecilia Oliveros Tiongson (ca 1867-1934)

- Feliciana Oliveros Tiongson (1869-1938)

- Alberta Santos Uitangcoy (1865-1953)

What happened to the school?

On February 20, 1889, the women finally received permission to open a school on certain conditions: First, the women were required to fund the school themselves since the government refused to. Second, their teacher would be Guadalupe Reyes rather than Sandiko, who had been blacklisted by Malolos’ friar-curate. Third, the classes would have to be held in the day and not at night, probably due to nighttime gatherings with subversive meetings.

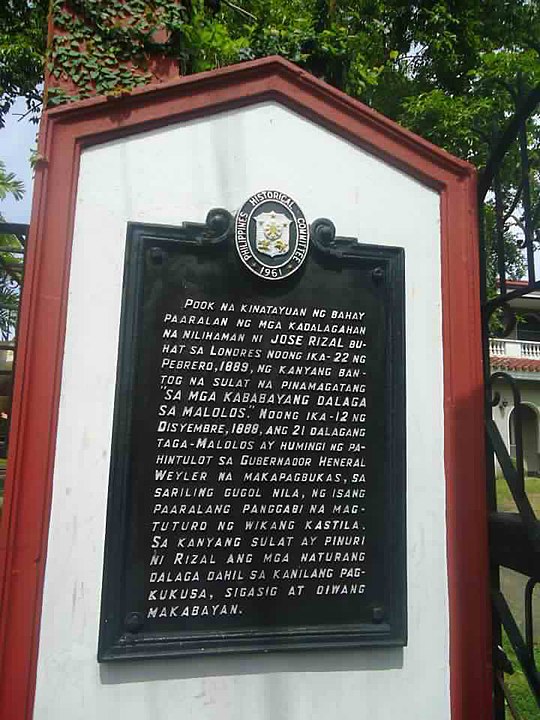

The school, called Instituto de Mujeres, was immediately opened in the home of one of the women, Rufina T. Reyes. However, the school was permanently closed down in May 1889, just three months after opening, due to the friars’ pressures. The school’s ruins and historical marker can still be found today at the end of Santo Niño street.

Which is which: 20 or 21?

The correct is 20, according to local historians, because 20 women signed and hand-carried the letter to Governor-General Valeriano Weyler, who was at the convent during his visit to Malolos on December 12, 1888.

References

- Tiongson, Nicanor G. The Women of Malolos. Ateneo De Manila University Press, 2004

- Aj. “Las Mujeres De Malolos.” #TTT10, 18 Sept. 2020, ajpoliquit.wordpress.com/2016/05/23/las-mujeres-de-malolos/

- City Government of Malolos, www.maloloscity.gov.ph/home/aboutus/historical-background.

- “Remember the Contributions of Women in History at This House-Turned-Museum.” NOLISOLI, 29 Feb. 2020, nolisoli.ph/10366/remember-the-contributions-of-women-in-history-at-this-house-turned-museum/

- “Rizal’s Letter: To the Young Women of Malolos (Full Copy).” Rizal, kwentongebabuhayrizal.blogspot.com/2013/07/to-young-women-of-malolos-full-copy.html.

- “The Heroism of the Malolos Women.” TravelSmart.NET, www.travelsmart.net/article/101153/

- “Rizal as a Ladies’ Man.” National Historical Commission of the Philippines, 4 Sept. 2015, nhcp.gov.ph/rizal-as-a-ladies-man/

- Facebook, www.facebook.com/PilipinasRetrostalgia/photos/get-to-know-the-women-of-malolosthe-women-of-malolos-consisted-of-20-women-from-/1665582083689682

- “Kadalagahan Ng Malolos: Prekursor Ng Peminismo – Kababaihan at Kasarian.” Google Sites, sites.google.com/site/kababaihanatkasarianpi100/diskusyonsamgaobranirizal/ang-liham-ni-rizal-sa-kadalagahan-ng-malolos

- KinoArts. YouTube, YouTube, 8 Mar. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=wiT8gobmkus

- “Dr. JOSE RIZAL.” The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ang Liham Ni Dr. Jose Rizal Sa Mga Kadalagahan Sa Malolos, Bulakan, by JOSE RIZAL., www.gutenberg.org/files/17116/17116-h/17116-h.htm

- “The Women of Malolos.” Create Infographic – Sign In, venngage.net/p/157700/the-women-of-malolos

- RAUSA-GOMEZ, LOURDES, and HELEN R. TUBANGUI. “Reflections on the Filipino Woman’s Past.” Philippine Studies, vol. 26, no. 1/2, 1978, pp. 125–141. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42632425. Accessed 4 Nov. 2020

- Ocampo, Ambeth R. “Malala and the Women of Malolos.” INQUIRER.net, 17 Oct. 2012, opinion.inquirer.net/38878/malala-and-the-women-of-malolos

Wow, wonderful weblog structure! How lengthy have you ever been running a blog for? you made running a blog look easy. The overall glance of your website is great, let alone the content material!!